Excess Reserves

Burying the Talents in the Backyard

In my days as a professor, I enjoyed parables. Parables are short narratives, useful in teaching a deeper meaning. One parable I often abuse is the parable of the talents found in the Gospel of Matthew. I’ll just mercilessly abuse the parables style and meaning to get to my point. A master leaves a certain amount of money, denoted in “talents” (hence the name of the parable), to his three servants. One takes the money to market, and gains returns. Another takes the money to the market and does okay. Probably not great, but not bad. The third however hid the money, and let it sit. He’s the one that got in trouble. But why? The Master had the same amount of money as before he left (I’m assuming Matthew, as a good tax collector was thinking in inflation-adjusted terms anyway). Well let’s mix our parables and include another great parable from Jimmy Stewart. In “It’s a Wonderful Life”, George Bailey averts a bank run by convincing his depositors not to withdraw all their money. The money isn’t there. It’s spread out throughout the town. It’s in the houses that their friends and neighbors have built. George Baily, as portrayed by Stewart, is the good and faithful servant of finance. The money he gets from depositors goes to helping the community of lenders, borrowers, spenders, and earners improve their lives by unlocking future value in the present (home loans, consumer loans, etc.). I always told my students that finance was the Lord’s work. Amen. But since the Great Depression, the financial institutions and the Federal Reserve tasked with getting returns on our talents have failed at their job. In fact they have jealously buried much of what could have been monetary stimulus in their backyards since the Great Recession. Let’s take a look at the Fed’s transmission mechanism, and the wicked and lazy primary dealer financial institutions that failed since 2008.

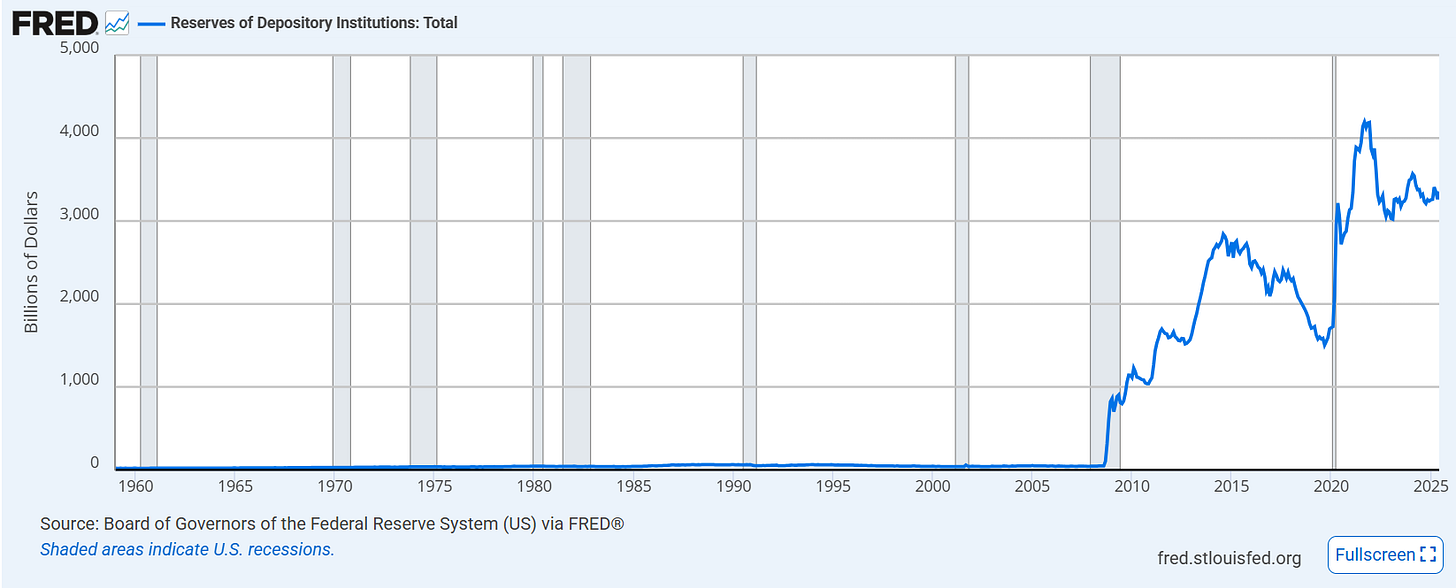

We should first talk about bank reserves. When you deposit your money at a bank, let’s say $100, the bank keeps some percentage back. They must do this to be supported by the Federal Reserve and federal government and minimize their risk in case of a bank run. But this is usually small. It used to be required to hold back more because banks would lose money if they kept reserves. Every dollar held back in reserves loses the opportunity to produce returns if it is loaned out. Banks have an incentive to lend out as much as possible. In fact, throughout most of the data history of reserves held by banks, banks kept a minimal amount of reserves. Between about 20 billion and 50 billion. Until 2008.

What this graph shows, is that banks went from holding about 50 billion in reserves, to holding 1 trillion by 2010, and nearly 3 trillion by 2015. They began to lend these reserves back out bit by bit, until Covid-19, when they kept over 4 trillion in reserves by 2021. Note that we still have not returned to pre-Covid level of returns, must less pre-2008.

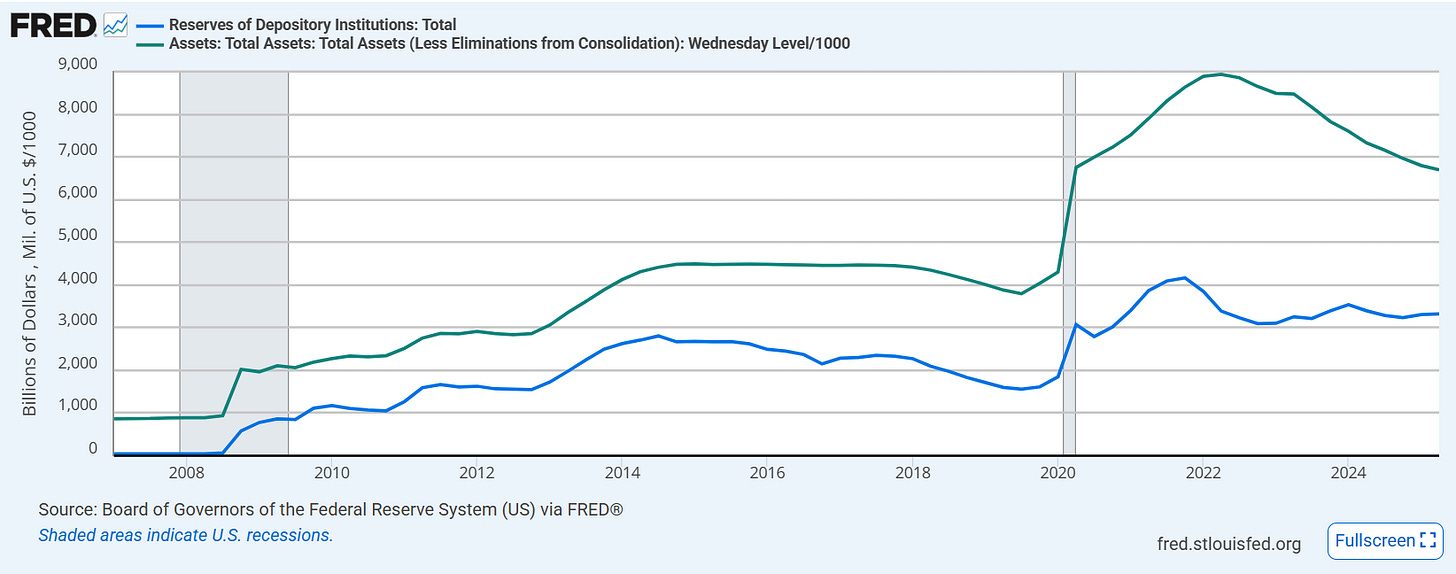

Where are they getting all this money? From the Fed. The Federal Reserve pushes out monetary stimulus not by increasing or decreasing interest rates (not directly) but through the money supply. Don’t confuse it. The money supply goes first, and interest rates follow. So, when the Fed wants to push 1.3 trillion dollars into the economy, it does so through buying assets from the “primary dealers”. These are the largest banks and financial institutions in the world: Goldman, Bank of America, Citi, Wells Fargo, Nomura, Deustche Bank. There are probably somewhere between 15 and 25 primary dealers any given year. These primary dealers are then supposed to take the money they now have from the Fed purchasing their assets (mortgage-backed securities for example) and use that to lend to the smaller banks they do business with. The idea is to maintain or increase liquidity during hard times. Except they haven’t done that since 2008.

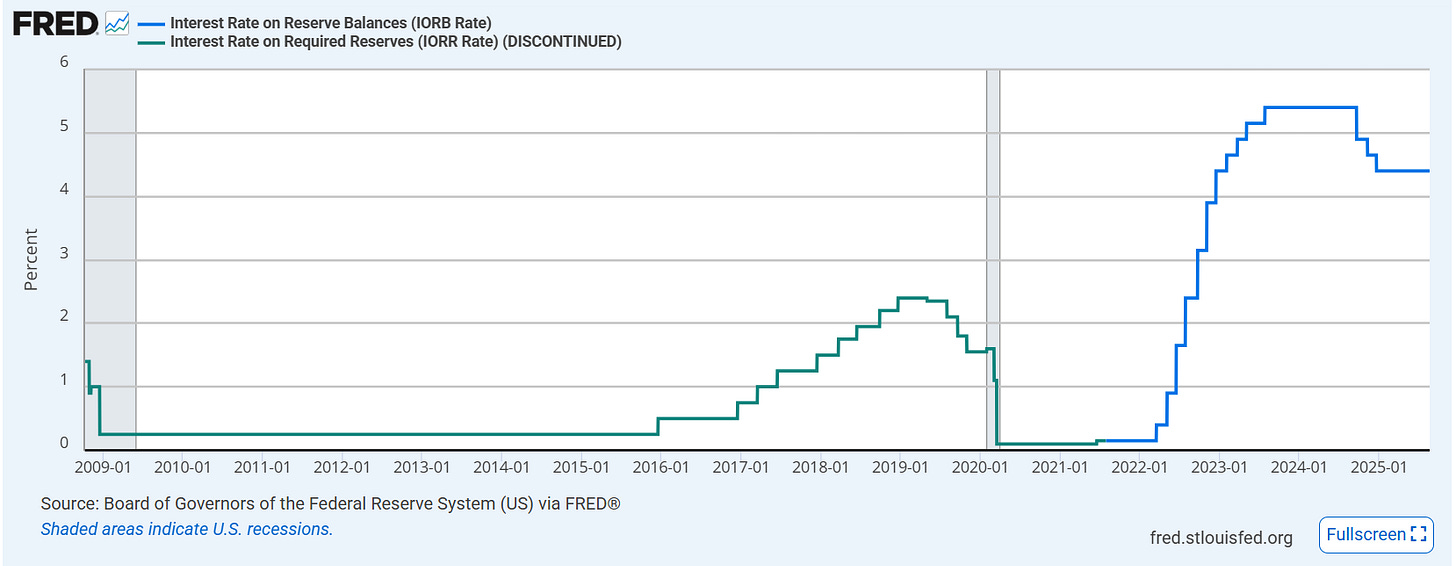

These wicked and lazy banks (as they would be described by Jesus, the author of the parable) are burying their talents in the back yard. That money is in the safe, not at Joe’s house, or the Kennedy’s house, or Ms. Macklin’s house. In fact, since 2008, the largest banks have been getting paid interest on these reserves by the Fed.

Now remember that stimulus money is supposed to be so that these banks feel better about lending to us. They are supposed to incentivize banks to loan so firms can weather the storm of the business cycle. But instead, the Federal Reserve is “printing” money, and the dozen-ish largest banks in the world are holding on to it and earning 4.4%. Let me repeat. Right now, the largest banks are refusing to lend money that was released from the Federal Reserve for the purpose of monetary stimulus for the past 15 years, to the tune of 4 trillion dollars, and earning a guaranteed 4.4% from the Fed on it. The transmission mechanism that was supposed to distribute monetary stimulus throughout the economy has been broken since 2008.

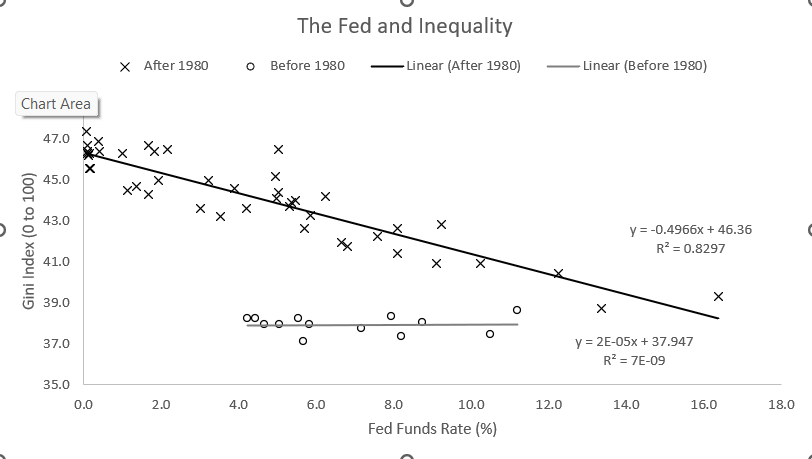

When I mentioned in the interview with our editor Glenn McMahan from Upriver Press for our new book Inequality by Design that monetary stimulus favors the wealthy, this is what I mean. Because the largest banks are not going to give good deposits or good loans to low income or middle-income households. And the largest banks are holding back the kind of lending they used to do with community and regional banks before the Great Recession; lenders who very well would lend to middle- or lower-income households at better rates. This is why we see since the 1980s the monetary stimulus policy enacted by the Fed coupling with the rising tide of inequality.

Before 1980 and before the consolidation and concentration of our banking system, the Fed Funds rate had zero correlation with the Gini measure of inequality. After 1980, it has a strong correlation to inequality.

The largest banks in the world have their finger on the scale of monetary policy. The Fed should bypass this antiquated and inefficient way of distributing stimulus. Monetary policy does not have to be at the cost of rising inequality.